- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

WASHINGTON — Ensuring access to high-quality primary care for all people in the United States will require reforming payment models, expanding telehealth services, and supporting integrated, team-based care, says a new report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. No federal agency currently has oversight of primary care, and no dedicated research funding is available. The report recommends the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) establish a Secretary’s Council on Primary Care and make it the accountable entity for primary care, as well as an Office of Primary Care Research at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Building on the recommendations of a 1996 report by the Institute of Medicine, the new report, Implementing High-Quality Primary Care: Rebuilding the Foundation of Health Care, provides an implementation plan for high-quality primary care in the U.S.

Pharmacists are more often being recognized as a critical component of the primary care team. Previous literature has not clearly made the connection to how pharmacists and comprehensive medication management (CMM) contribute to recognized foundational elements of primary care. In this reflection, we examine how the delivery of CMM both supports and aligns with Starfield’s 4 Cs of Primary Care. We illustrate how the delivery of CMM supports first contact through increased provider access, continuity through empanelment, comprehensiveness by addressing unmet medication needs, and coordination through collaborating with the primary care team and broader team. The provision of CMM addresses critical unmet medication-related needs in primary care and is aligned with the foundational elements of primary care.

Background:

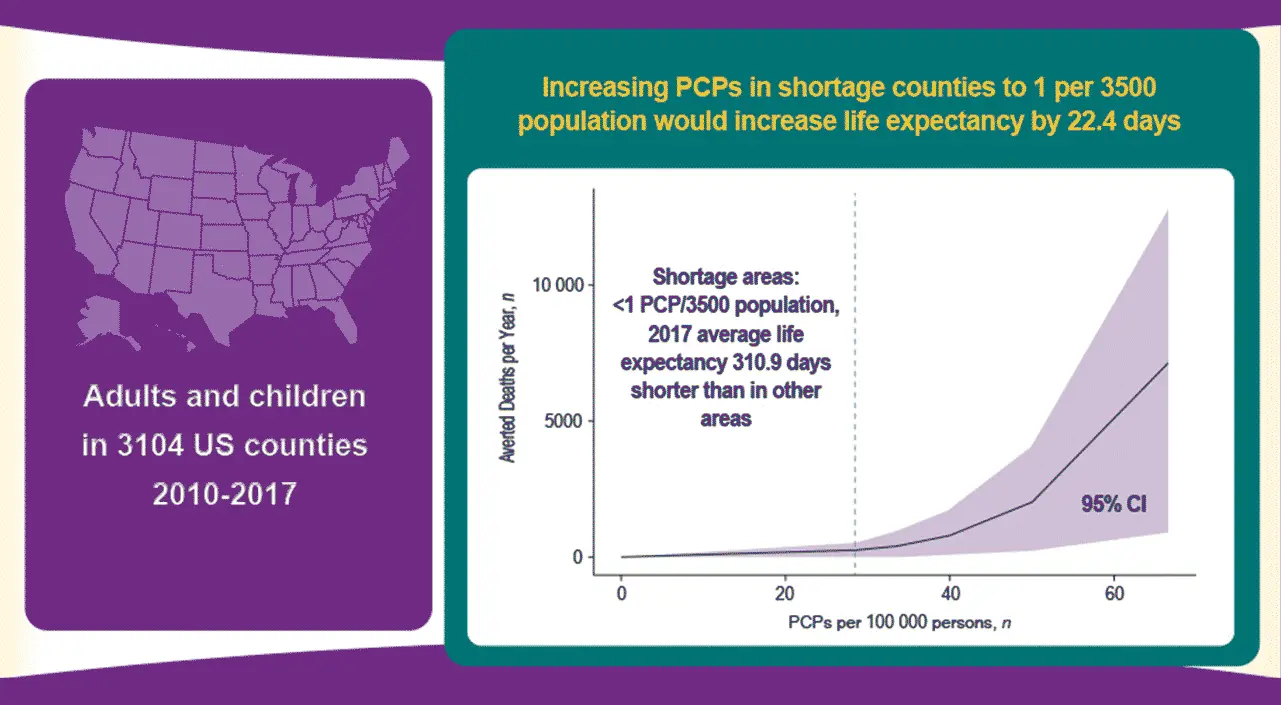

Prior studies have reported that greater numbers of primary care physicians (PCPs) per population are associated with reduced population mortality, but the effect of increasing PCP density in areas of low density is poorly understood.

Objective:

To estimate how alleviating PCP shortages might change life expectancy and mortality.

Design:

Generalized additive models, mixed-effects models, and generalized estimating equations.

Setting:

3104 U.S. counties from 2010 to 2017.

Participants:

Children and adults.

Measurements:

Age-adjusted life expectancy; all-cause mortality; and mortality due to cardiovascular disease, cancer, infectious disease, respiratory disease, and substance use or injury.

Results:

Persons living in counties with less than 1 physician per 3500 persons in 2017 had a mean life expectancy that was 310.9 days shorter than for persons living in counties above that threshold. In the low-density counties (n = 1218), increasing the density of PCPs above the 1:3500 threshold would be expected to increase mean life expectancy by 22.4 days (median, 19.4 days [95% CI, 0.9 to 45.6 days]), and all such counties would require 17 651 more physicians, or about 14.5 more physicians per shortage county. If counties with less than 1 physician per 1500 persons (n = 2636) were to reach the 1:1500 threshold, life expectancy would be expected to increase by 56.3 days (median, 55.6 days [CI, 4.2 to 105.6 days]), and all such counties would require 95 754 more physicians, or about 36.3 more physicians per shortage county.

Limitation:

Some projections are based on extrapolations of the actual data.

Conclusion:

In counties with fewer PCPs per population, increases in PCP density would be expected to substantially improve life expectancy.

Primary Funding Source:

None.